Walden University

ScholarWorks

"&&%''#"&"#'#% '(&

"&&%''#"&"#'#% '(&

# '#"

Domestic Violence Recidivism: Restorative Justice

Intervention Programs for First-Time Domestic

Violence O!enders

Tamika L. Payne

Walden University

# #*'&"'#" *#%&' .$&&# %*#%&* "((&&%''#"&

%'#' %!"# #+#!!#"& %!"# #+"%!" (&'#!!#"&"'

("''')( '')#!$%')"&'#% '## #&#!!#"&

-&&&%''#"&%#(''#+#(#%%"#$"&&+' "&&%''#"&"#'#% '(&# '#"'# %#%&'&"

$'#%" (&#"" "&&%''#"&"#'#% '(&+"('#%,!"&'%'#%## %#%&#%!#%"#%!'#"$ &

#"'' # %#%&* "((

Walden University

College of Social and Behavioral Sciences

This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by

Tamika Payne

has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects,

and that any and all revisions required by

the review committee have been made.

Review Committee

Dr. Barbara Benoliel, Committee Chairperson, Human Services Faculty

Dr. Tina Jaeckle, Committee Member, Human Services Faculty

Dr. Gregory Hickman, University Reviewer, Human Services Faculty

Chief Academic Officer

Eric Riedel, Ph.D.

Walden University

2017

Abstract

Domestic Violence Recidivism: Restorative Justice Intervention Programs for First-Time

Domestic Violence Offenders

by

Tamika L. Payne

MA, University of Cincinnati, 2010

BS, Old Dominion University 2007

Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Human Services

Walden University

June 2017

Abstract

Domestic violence impacts millions of Americans annually and, in spite of the use of

rehabilitative programs, recidivism in domestic violence continues to be more likely than

in any other offense. To date, batterer intervention programs (BIPs) have not proven to

be consistently impactful in reducing recidivism in cases of domestic violence. The

purpose of this quasi-experimental, quantitative study was to examine differences in

recidivism for first-time male domestic violence offenders who have participated in a BIP

and a more recently developed alternative: victim-offender mediation (VOM). The

theories of restorative justice and reintegrative shaming frame this study to determine if

offenders take accountability for their actions and face the victim in mediation, there can

be a reduction in recidivism. Archival data from records of first-time male, domestic

violence offenders, between the ages of 18 and 30, who participated in either a VOM or

BIP in a county in the Midwest were examined for recidivism 24-months

postintervention, and analyzed with an ANCOVA analysis while controlling for age. The

findings revealed no significant difference in recidivism for first-time male offenders 24-

months post participation in a BIP or a VOM intervention while controlling for age F

(1,109) =.081, p = .777. The findings provide support for the notion that restorative

justice interventions may be an additional intervention used in cases of domestic violence

deemed appropriate for the intervention. The findings from this study can add to the body

of research examining interventions to address the high recidivism in cases of domestic

violence, which impacts victims, offenders, and communities.

Domestic Violence Recidivism: Restorative Justice Intervention Programs for First-Time

Domestic Violence Offenders.

by

Tamika L. Payne

MS, University of Cincinnati, 2010

BS, Old Dominion University. 2007

Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Human Services

Walden University

June 2017

Dedication

I would like to dedicate this study to my grandmothers Faye Payne and Marian Williams

who have truly been examples of strength and courage for me throughout my life. I

would also like to dedicate this to my mother who has been my strength throughout the

journey. And last but not least to my husband, Melvin for the continual love and

encouragement.

i

Table of Contents

List of Tables .......................................................................................................................v

List of Figure...................................................................................................................... vi

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Study ....................................................................................1

Background ....................................................................................................................4

Problem Statement .........................................................................................................6

The Purpose of the Study ...............................................................................................9

Nature of the Study ........................................................................................................9

Research Question .......................................................................................................10

Hypotheses ...................................................................................................................10

Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................10

Definition of Key Terms ..............................................................................................15

Assumptions, Limitations and Delimitation ................................................................16

Significance of the Study .............................................................................................17

Social Change Implications .........................................................................................18

Summary ......................................................................................................................18

Chapter 2: Literature Review .............................................................................................20

Research Strategy.........................................................................................................20

Domestic Violence .......................................................................................................21

Prevalence of Domestic Violence Incidents in the United States ......................... 22

Victims .................................................................................................................. 23

Offenders............................................................................................................... 26

ii

Mental Health and Substance Abuse .................................................................... 28

Domestic Violence Laws .............................................................................................29

International .......................................................................................................... 29

Recidivism ...................................................................................................................32

RJI and Recidivism Demographics ....................................................................... 34

Interventions ................................................................................................................34

Schools of thought .......................................................................................................36

Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................41

Restorative Justice ................................................................................................ 41

Reintegrative Shaming .......................................................................................... 44

Summary ......................................................................................................................48

Chapter 3: Research Method ..............................................................................................50

Procedures ....................................................................................................................50

Research Design and Rationale ...................................................................................52

Methodology ................................................................................................................53

Data Analysis Plan .......................................................................................................55

Archival Data ...............................................................................................................55

Variables of the study ..................................................................................................56

Recidivism ............................................................................................................ 56

Victim-offender mediation.................................................................................... 57

Batterer intervention program ............................................................................... 57

Age ................................................................................................................... 57

iii

Operational Definition of Variables .............................................................................58

Research Question .......................................................................................................59

Hypotheses ...................................................................................................................59

Threats to validity and limitations ...............................................................................59

Ethical Assurances .......................................................................................................61

Assumptions .................................................................................................................61

Summary ......................................................................................................................62

Chapter 4: Results ..............................................................................................................63

Introduction ..................................................................................................................63

Data Collection ............................................................................................................63

Results ..........................................................................................................................64

Summary ......................................................................................................................68

Chapter 5: Discussion, Conclusion, and Recommendations .............................................69

Introduction ..................................................................................................................69

Interpretation of the Findings.......................................................................................69

Recidivism ............................................................................................................ 70

VOM ................................................................................................................... 71

BIP ................................................................................................................... 72

Age ................................................................................................................... 73

Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................74

Limitations of the Study...............................................................................................76

Discussion ....................................................................................................................78

iv

Recommendations ........................................................................................................80

Implications..................................................................................................................81

Conclusion ...................................................................................................................82

References ..........................................................................................................................83

v

List of Tables

Table 1. Levene’s Test of Equality of Error Variance………….......................................66

Table 2. Analysis of Covariance Summary………………………………..…………….67

vi

List of Figure

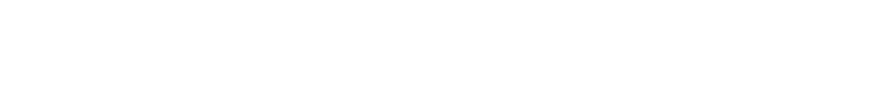

Figure 1. Estimated marginal means ................................................................................ 65

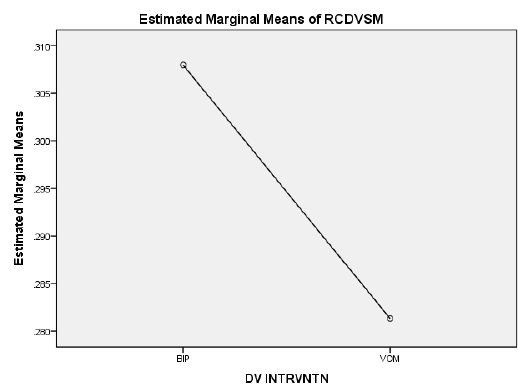

Figure 2. Normal Q-Q Plot RCDVSM for VOM ............................................................. 66

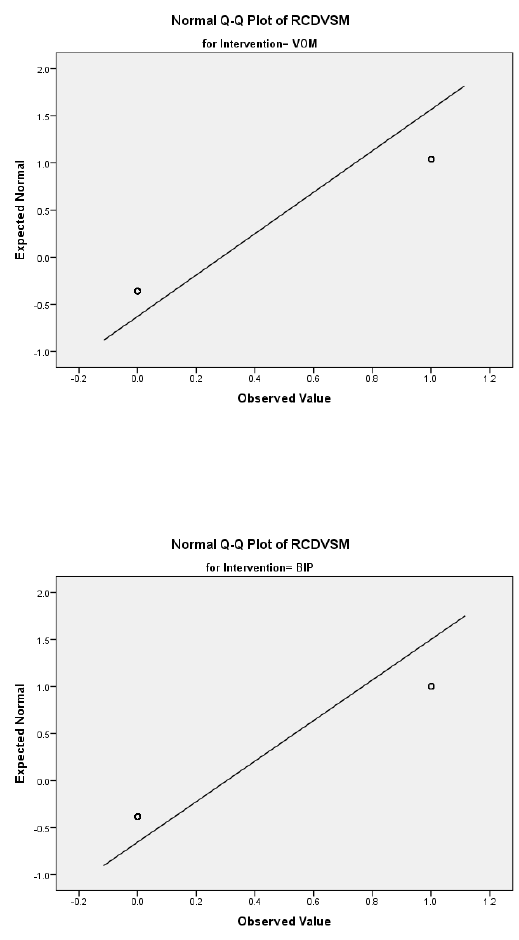

Figure 3. Normal Q-Q Plot for RCDVSM BIP................................................................. 66

1

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Study

Recidivism in cases of domestic violence in the United States occurs at a higher

rate than other violent crimes, despite the use of interventions such as protection orders,

probation, incarceration, and batterer intervention programs (Frantzen, Miguel, & Kwak,

2011; Mills, Barocas, & Ariel, 2013; Richards, Jennings, Tomsich, & Gover, 2014; Sloan,

Platt, Chepke, & Blevins, 2013). Furthermore, incidents of domestic violence are higher

in age groups 18-24, which correlates with statistics representing the prevalence of crime

by age (Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black, & Mahendra, 2015; Nelson, 2013). Domestic

violence offenders enter the criminal justice system once charged with the crime of

domestic violence (Frantzen et al., 2011).

Interventions for domestic violence offenders in situations deemed appropriate by

providers include victim–offender mediation (VOM), a restorative justice intervention

(RJI; Mills et al., 2013). Another intervention used was a batterer intervention program

(BIP; Mills et al., 2013). BIPs are the most commonly used programs for domestic

violence offenders; programs are modeled after the Duluth program developed in the

1980s by Ellen Pence and Michael Paymar (Pender, 2012). The BIP model was a group-

oriented therapeutic behavior modification treatment focusing on contributing factors of

domestic violence including anger and control (Pender, 2012). BIPs have been shown to

be effective in the reduction of recidivism as compared to traditional sanctions including

arrest, probation, and incarceration (Mills et al., 2013; Pender, 2012; Sherman & Harris,

2013).

2

VOM programs differ from BIPs, as VOM programs are a form of restorative

justice mediation between the victim and offender (Daly, 2012; Dhami, 2012; Gromet,

Okimoto, Wenzel, and Darley, 2012; Weeber, 2012). Present during the mediation session

in addition to the victim, offender, and mediator was also the prosecuting attorney, and

any other appropriate court officials (Daly, 2012; Dhami, 2012; Gromet, 2012; Weeber,

2012). VOMs are initiated through the request of the victim, and thereafter a certified

mediator or court official completes an evaluation to determine if the mediation was

appropriate (Daly, 2012; Dhami, 2012; Gromet, 2012; Weeber, 2012). Some factors that

are examined to determine appropriateness are the severity of the crime and willingness

of the offender to participate in the mediation (Daly, 2012; Dhami, 2012; Gromet, 2012;

Weeber, 2012). In some cases, VOM programs are combined with other treatments and

interventions to include BIPs, probation, and incarceration (Dhami, 2012). When

examining recidivism with the use of VOMs and BIPs, both programs have been shown

to reduce reconviction of domestic violence offenders (Mills et al., 2013; Sloan et al.,

2013). Despite these findings, VOMs are not as commonly used as BIPs as an

intervention in cases of domestic violence.

In research examining restorative justice (RJ) interventions such as VOM,

researchers found in two different research studies, that possible reasons for the limited

use of VOM were limited research on VOM outcomes within the criminal justice field,

the impact of VOM on victims, and legal professionals’ preference for punitive methods

(Gavrielides, 2015; Mills et al., 2013). Concerns regarding the victim arise because the

construct of VOM typically involves a session involving the victim, the offender, a

3

criminal justice representative, and a mediator to discuss the crime and come to an

agreed-upon resolution (Daly, 2012; Dhami, 2012; Gromet, 2012; Weeber, 2012).

Despite such reservations about the use of VOM in domestic violence cases, the

intervention has proved impactful in reducing recidivism in other violent crimes

(Mongold & Edwards, 2014). VOM was most commonly used as an intervention with

nonviolent offenses and with juveniles (Mongold & Edwards, 2014). Researchers have

recognized that RJIs are not appropriate in all cases of domestic violence, and should be

considered on a case by cases basis, taking into consideration the severity of the abuse

and victim willingness to participate (Gavrielides, 2015). In this study, I compared VOM

to BIP to examine the differences of each intervention on recidivism.

In a previous study, Nelson (2013) found that there was a correlation between

committing crimes and the age of the offender, which has also been examined regarding

domestic violence crimes. In research examining recidivism in cases of domestic

violence, Nelson (2013) found that convictions for crimes of domestic violence

significantly decreases after the age of 30. The researcher, Nelson (2013) concluded that

recidivism occurs because of aging, and that research should exclude age when

examining the effectiveness of intervention. In the study by Nelson (2013), the researcher

controlled for age in the comparison of recidivism between VOM and BIP interventions.

This chapter included an introduction to the problem of recidivism in domestic

violence cases. I provided an explanation of the background of the issue, the purpose of

the study, and hypothesized outcomes of this research. In this chapter I also included

definitions of terms used throughout the study, along with limitations, assumptions, and

4

social implications of the study. A detailed literature review and theoretical framework

are presented in Chapter 2. Chapter 3 includes a discussion of the methodology used in

the completion of this quantitative quasi-experimental study. I present the discussion of

the findings in Chapter 4, and present the conclusions in Chapter 5.

Background

Researchers Herman, Rotunda, Williamson, and Vodanovich (2014) estimated that

approximately 1.3 million women and 750 thousand men are affected by domestic

violence in the United States annually (Herman, Rotunda, Williamson, & Vodanovich,

2014). In 2012, there were 51,644 charges of domestic violence in the United States—an

increase of 12.6% from 2011 (Cucinelli, 2014). Nationally, from 2003 to 2012, domestic

violence accounted for 21% of all violent crimes (Truman & Morgan, 2014). With these

high rates, interventions are needed to provide protection for victims. Domestic violence

figures have remained high despite the use of various interventions to treat offenders.

The results of studies on domestic violence interventions Mills et al. (2013),

Pender, (2012), Sloan et al. (2013) have suggested that formal sanctions (e.g., restraining

orders, probation, and incarceration) are not effective in the reduction of recidivism.

Researchers Mill, Barocas, and Ariel have shown that BIPs are more efficient than formal

sanctions in reducing recidivism. In other findings researchers suggested that RJIs may

also be more effective in reducing recidivism than formal sanctions (Mills et al., 2013). In

a study comparing circles of peace (CPs; a form of VOM) and BIPs, researchers found

that in a 6-month period, CPs were more effective in reducing recidivism in offenders

(Mills et al., 2013). However, long-term results were not significant enough to indicate

5

that CPs were more effective, and there were questions about the effectiveness of other

RJIs (Mills et al., 2013).

BIPs and VOMs are two of four commonly used interventions used in response to

cases of domestic violence offenders, in addition to anger management and individual

therapy (Daly, 2012; Dhami, 2012; Gromet, 2012; Weeber, 2012). Offender participation

in a BIP is determined through assessment, addressing the nature of the offense and other

factors to determine appropriateness (Pender, 2012). There have been reductions in

recidivism among domestic violence offenders where BIPs have been used (Mills et al.,

2013).

In this study, I compared differences in recidivism rates for first-time male

offenders in VOM versus BIPs; I addressed questions from previous studies on the

effectiveness of the interventions as measured by reduction in recidivism. I examined

data ex post facto, with a particular focus on first-time male offenders between the ages

of 18 and 30, which is deemed to be the population with the highest recidivism rates in

cases of domestic violence (Renner, Whitney, & Vasquez, 2015; Richards et al., 2014;

Sutton, Simons, Wickrama, & Futris, 2014). The factors that were addressed in the

study—VOM, and BIPs—have not previously studied together in the context of

recidivism in first-time, male, domestic violence offenders. The aim of this study was to

determine if there was a significant difference in recidivism rates for first-time male

offenders enrolled in a VOM intervention or a BIP program without participation in

VOM.

6

Problem Statement

Despite the use of interventions in cases of domestic violence, recidivism remains

a concern (Apel, 2013; Herman et al., 2014; Mills et al., 2013). Apel (2013), in a study

examining formal sanctions’ effect toward criminal deterrence, researchers indicated that

formal sanctions such as probation, incarceration, and capital punishment do not have a

statistically significant effect in the deterrence of some crimes, including violent crimes

such as domestic violence. Further, formal sanctions within a punitive model of justice

can lead to additional harm and vengeance (Wozniak, 2014). In a study by Herman et al.

(2014), researchers found that, after completion of a BIP, approximately 37.4% of the

offenders reoffended. The researchers suggested that one reason for the program’s

ineffectiveness was that the BIP addressed the criminal and legal aspects of the crime,

rather than behaviors (Herman et al., 2014). RJ programs created an opportunity for

resolution between the victim and offender, through the examination of the motivation for

the crime and appropriate interventions (Morrison & Vaandering, 2012). In comparison,

RJI programs focused on offenders’ behaviors and their impact on the victim, offender,

and community (Morrison & Vaandering, 2012).

Despite findings from research studies were researchers have found significance

in reduction of recidivism for domestic violence offenders in RJI programs, during the

research period ending in 2012, RJI programs were not chosen as interventions for

domestic violence cases by judges, and lawyers n many criminal justice agencies in cases

of domestic violence (Alarid & Montemayor, 2012). A factor contributing to decreased

use of RJI programs has been mandatory arrest laws that mandate traditional punitive

7

legal actions for domestic violence offenders (Boal & Mankowski, 2014). As a result of

mandatory arrest laws, there has been an increase in BIPs, as these programs can be

mandated and monitored by probation officers (Boal & Mankowski, 2014). Although

mandatory arrest laws provided an immediate decrease in danger for victims, many

feminists argue that victims are placed at a greater risk of danger upon the offender's

release from jail (Munjal, 2012). Despite the increase in interventions and legal sanctions

in cases of domestic violence, recidivism rates for these crimes remain amongst the

highest for violent offenses (Alarid & Montemayor, 2012, Morrison & Vaandering,

2012). The high recidivism rates not only impact victims, but also the criminal justice

system with the financial cost, medical costs, and communities (Bell, Cattaneo,

Goodman, & Dutton, 2013; Juodis, Starzomski, Porter, & Woodworth, 2014).

Mills et al. (2013) suggested that there has been limited research examining

recidivism in domestic violence cases with the use of RJIs. In their study, Mills et al.

compared recidivism for offenders enrolled in either a BIP or an RJI CP over a 24-month-

period. CP interventions were group sessions involving victims, offenders, criminal

justice officials, and family members to address the issue of violence and find a

resolution (Mills et al., 2013). The participants in Mills et al.’s study were individuals

charged with misdemeanor domestic violence offenses; some had previously been

charged with a domestic violence offense.

In addition, there has been limited research examining recidivism while

controlling for age. In a study by Nelson (2013) examining recidivism and sentencing

practices, the researcher found that age was a significant factor in the reduction of

8

recidivism. Researchers found in previous studies that crime decreases with age (Breiding

et al., 2014; Nelson, 2013). In a study examining domestic violence, the researcher

concluded similar findings, that suggest that age should be a controlled variable when

examining if interventions are correlated to the reduction of recidivism (Nelson, 2013).

In the study by Richards et al., it was found that repeat domestic violence

offenders were more likely to reoffend than those charged for the first offense (Richards

et al., 2014). Over a 10-year period, multiple-time domestic violence offenders who were

charged with domestic violence were more likely to reoffend than first-time offenders

(Richards et al., 2014). One common theme remains: RJIs can be the most effective

response in certain cases of domestic violence (Gavrielides, 2015). Researchers

examining the use of RJIs found a reduction in recidivism for violent offenders who have

committed crimes similar to domestic violence, such as assault and battery (Morrison &

Vaandering, 2012).

Although the aforementioned research regarding recidivism in cases of domestic

violence contains significant findings, I have found limited research on recidivism rates

while controlling for age in cases of first-time male domestic violence offenders who

participated in the RJI VOM programs. Thus, further research was warranted on

recidivism in cases of domestic violence for first-time male offenders enrolled in RJI

programs in comparison with BIPs. The limited amount of research in this area highlights

the need for additional studies regarding recidivism in cases of domestic violence with

the use of RJIs (Sloan et al., 2013).

9

The Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this quasi-experimental quantitative study was to examine

differences in recidivism between offenders enrolled in a BIP and offenders enrolled in a

VOM program, while controlling for age. My goal was to examine the impact of

restorative justice interventions on domestic violence in a population that has been

deemed high risk for violent crimes. By examining the differences, the outcomes could

support the use of alternative interventions in cases of domestic violence. The

participants consisted of male offenders age 18-30 years. The timeframe of the

examination was a 2-year period following completion of the VOM or BIP program

(2012 through 2013). The results of this study could provide a better understanding of

strategies to address recidivism in cases of domestic violence.

Nature of the Study

The study involved quantitative, quasi-experimental analysis of archival data. A

quantitative, quasi-experimental design was the most appropriate for the proposed study,

as this method allows for examination of differences ex post facto for variables not

randomly assigned. The use of an ANCOVA analysis made it possible to examine the

differences between the dependent variable recidivism rates for two levels of the

independent variable, VOM and BIPs, in a region where both interventions are available

and in use, while controlling for the covariate, age, the second independent variable.

Using an existing database, I could track outcomes over a period of time.

10

Research Question

RQ: What is the difference between recidivism rates for offenders who have

participated in the restorative justice intervention VOM versus those who have

participated in a BIP for first-time male domestic violence offenders 24 months

postintervention?

Hypotheses

In this study, I examined the differences in recidivism for first-time male domestic

violence offenders in VOM versus BIP programs, while controlling for age. Recidivism

data were examined at 24 months’ post-intervention. The hypotheses are as follows:

Ho: µ1=µ2: There are no differences in recidivism rates between offenders

enrolled in VOM versus BIP at 24 months’ postintervention, while controlling for age,

H1: µ1 ≠ µ2: There are differences in recidivism rates between offenders enrolled

in VOM versus BIP at 24 months’ postintervention, while controlling for age.

Theoretical Framework

In this study, I examined recidivism for first-time male domestic violence

offenders who have participated in VOM, a restorative justice intervention program, as

well as a BIP. The theory of RJ relies upon an understanding of behavior through a

motivational and socialization viewpoint (Morrison & Vaandering, 2012). The basis of

the theory was that an individual’s motivation to commit crimes was contingent on how

committed they are to society (Morrison & Vaandering, 2012). Examples of commitment

included community, family, and friends, in addition to social norms. Several theories of

RJ posit different constructs about the criminal justice system (Daly, 2013; Kenny &

11

Leonard, 2014; Morrison & Vaandering, 2012; Weeber, 2012). The commonality among

the theories is the notion that social commitment plays a role in an individual’s

motivation not to commit crimes (Morrison & Vaandering, 2012).

The practice of RJ dates back to 68000 BC a time when human societies did not

have a formal criminal justice system (Dickerson-Gilmore, 2014). In societies where the

criminal justice system is structured around RJ principles, the victim and offender

worked together to address the issue, with the intended outcome of justice for the victim

and reduction in reoffending for the offender (Dickerson-Gilmore, 2014).

RJIs can be conducted in different ways to include family sessions, community

service, and victim and offender mediation (Beck, 2015; Gavrielides, 2015;

Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015). VOM, one type of RJI, involves mediation between

the victim and offender to restore power to the victim through the victim’s participation

in court proceedings, and communication with the offender on punishment for the crimes

(Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015). The anticipated outcome of recidivism was that there

would be a reduction in the likelihood of reoffending, as the offender would take

accountability for actions (Gavrielides, 2015; Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015). Because

RJI did not encourage formal criminal justice procedures, VOM, like other RJ

approaches, was not widely used due to negative viewpoints of the nonpunitive

components of the interventions (Gavrielides, 2015; Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015).

In cases of domestic violence, reservations concerning the use of VOM have been

based on limited research on the impact of VOM on victims (Gavrielides, 2015;

Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015; Mills et al., 2013). Power and control dynamics that

12

are associated with the crime of domestic violence, and could be harmful to victims, was

determined by judges and lawyers to be another concern (Gavrielides, 2015;

Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015; Mills et al., 2013). Because of the power and control

dynamics in cases of domestic violence, VOM may not be appropriate, as victims may

become revictimized due to the mediation session (Gavrielides, 2015; Laxminarayan &

Woldhuis, 2015; Mills et al., 2013). Because of the nature of domestic violence crimes,

the victim must be willing to participate and the environment must be safe for all parties

involved (Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015). As a result of the limited use of VOM

programs, there have not been many opportunities to perform research studies on victims

or to examine the effects of VOM on offenders (Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015).

Another reservation regarding the use of the VOM approach includes the

appropriateness of the use of RJIs for more violent crimes, including domestic violence.

Researchers have taken into consideration that RJIs are not appropriate to use in all cases

of domestic violence, and interventions such as BIPs are more appropriate when the

victim does not want to participate, and there has been a lethal level of violence

(Sherman, Strang, Mayo-Wilson, Woods, & Ariel, 2015). An example of inappropriate

cases determined by previous research are cases where there are significant violent

threats, and when the victim is not comfortable with the mediation (Sherman et al., 2015).

Despite these reservations, RJ theorists have proposed that the intervention is appropriate

in cases where a designated individual screened the victim and offender for suitability for

the intervention (Gavrielides, 2015; Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015; Mills et al., 2013).

Researchers found RJIs to be more cost-effective than formal sanctions, which is an

13

additional benefit of using the intervention (Sherman et al., 2015). Researchers

determined cost by the nature of the crime and cost associated with recidivism (Sherman

et al., 2015).

To further explain recidivism, the theory of reintegrative shaming, developed by

Braithwaite (1989), may be applied to describe offenders’ behaviors. Reintegrative

shaming encompasses the idea that criminals who come to feel shame and remorse, and

are held accountable for actions by the members of their community who also care for

them, are less likely to engage in criminal behaviors than individuals who have received

punishment based on the crime and have reformed (Braithwaite, 1989; Mongold &

Edmonds, 2014). Developers of VOM interventions focused on the individual accepting

the criminal behaviors while also working toward reparations for actions, which was a

principle of reintegrative shaming (Dhami, 2012). VOM interventionist used theoretical

approaches to further understand the differences in the outcome between recidivism and

VOM as compared to BIPs.

Similar to RJ, researchers have used reintegrative shaming in cases of violence

and with juveniles (Mongold & Edwards, 2014). Reintegrative shaming focuses on the

crime, the use of shame by the people who the offender deems significant, such as their

family members, and reintegration to reduce crime (Braithwaite, 1989). Reintegrative

shaming theory suggests that once a crime has occurred, the offender should be held

accountable for behaviors; which should occur in a manner where respect is exhibited

(Braithwaite, 1989; Mongold & Edmonds, 2014). The intervention should lead to the

offender feeling shame and remorse for actions to those whom the offender holds dear,

14

then the offender should be openly reintegrated back into society (Braithwaite, 1989;

Mongold & Edmonds, 2014). Reintegrative shaming is a theory that focuses on the

importance of socialization, based on the position of disapproval of the actions associated

with rituals of forgiveness (Braithwaite, 1989). Mongold and Edmonds related

reintegrative shaming to VOM, as reintegrative shaming focuses on offenders

understanding the impact of their actions and making amends to society for wrongdoing

in reintegration efforts (Braithwaite, 1989; Mongold & Edmonds, 2014). Consideration,

according to theorist should be taken as every offender cannot be reintegrated back into

society (Mongold & Edmonds, 2014).

BIP and VOM interventions both focus on intervention in the behaviors of

offenders, with the goal of reducing recidivism (Dhami, 2012; Herman et al., 2014).

Interventions influenced by reintegrative shaming focus on reduction in recidivism by

addressing how individuals are socialized in society (Braithwaite, 1989). By combining

careful family focused shaming with reintegration, Braithwaite (1989) intended to have

individuals take accountability for crimes and learn that criminal behaviors do not meet

social norms. For persons who commit crimes of domestic violence, punitive shaming

can occur through measures such as arrest and filing of charges and this may lead to

anger and distrust, not reintegration. The difference between reintegrative shaming and

punitive shaming is that reintegrative shaming leads offenders to feel remorseful and

engaged in society, while punitive shaming can lead to anger and isolation (Braithwaite,

1989).

15

RJIs, in cases of domestic violence, may be effective in reducing recidivism when

used post-conviction (Miller & Iovanni, 2013). These findings not only suggest that

victims have more time to heal when RJ occurs post-conviction but also that offenders

may develop empathy and understanding of the crime (Miller & Iovanni, 2013). The

findings further suggest that as a result of reintegrative shaming (accountability),

offenders are better able to understand that domestic violence incidents do not meet

societal norms. Reintegrative shaming theory provides concepts to address recidivism

and socialization concerns about the crime of domestic violence (Braithwaite, 1989;

Dhami, 2012; Herman et al., 2014; Miller & Iovanni, 2013).

Definition of Key Terms

Batterer intervention program (BIP): A group intervention program for domestic

violence offenders that is mandated by the courts to address behaviors associated with

domestic violence (Mills et al., 2013). Programs are 26 weeks in length and include anger

management, and self-control techniques (Mills et al., 2013).

Domestic violence: An act of violence committed by an individual against an

intimate partner or family member (Breiding et al., 2014).

Male Offenders: Male individuals who have been charged with the crime of

domestic violence against an intimate partner during the reporting period as identified in

the study (Breiding et al., 2014).

Recidivism: A repeat offense resulting in a charge of domestic violence within the

24 months’ post-intervention (Herman et al., 2014).

16

Victim–offender mediation (VOM): A restorative justice intervention between the

victim, offender, and court officials in a structured environment to address the details of

the crime and agreed-upon sanctions (Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015).

Assumptions, Limitations and Delimitation

In this study, I made several assumptions. One assumption was that the

participants would be representative of the population for the geographical location. For

example, I assumed that the participants of first-time male domestic violence offenders

enrolled in VOM and BIP would be similar to other first-time male offenders enrolled in

similar programs. Second, as archival data were collected, I assumed that the data were

accurate and of high quality. High quality data collected was collected to meet the

standards set for research and the requirements for the study. Thirdly, as I conducted an

ANCOVA analysis I assumed that there was linearity, homogeneity of variance, normal

distribution, and independence (Field, 2013).

The scope of this study is the examination of recidivism for offenders who

participated in a BIP or VOM program. The offenders were male, first-time offenders, in

the State of Ohio, who had been convicted of a crime of domestic violence and were

between the ages of 18 and 30. I collected data from the municipal court in Franklin

County, Ohio, including information from 2013. The design of the study was a quasi-

experimental analysis of archival data. I did not collect the data while participants were in

a BIP or VOM program. The limitations of the study include the chosen data collection

method, which may limit factors that might further explain recidivism. In addition, I did

not collect data while offenders participate in the programs, the data were secondary data

17

compiled by the Franklin County Municipal Court in Ohio, rather than by the researcher

for this research. Franklin County Municipal Court clerks collected the data, and I did not

have control over the criteria for participants placed in the programs. I also did not have

control on the accuracy of the information that is collected.

A delimitation of the study was controlling for the age of the participants; this

study excluded the population under 18 and over the age of 30. Another delimitation was

that the study included only first-time domestic violence offenders and did not include

repeat offenders. The sex of the offenders was male, which was also a delimitation.

Significance of the Study

In the United States, domestic violence affects thousands of families each year,

and the majority of domestic violence cases go unreported (Alarid & Montemayor, 2012).

There are interventions in place with the goals of decreasing recidivism among domestic

violence offenders and promoting the rehabilitation of these offenders, but recidivism

rates remain high (Mills et al., 2013). Mills et al. (2013), in a comparison of a BIP and

RJI CPs, found no significant difference in recidivism rates between the CP and BIP.

Mills et al. concluded that the RJI was effective in reducing recidivism for domestic

violence offenders at the same rate as the BIPs. The significant differences between RJIs

and BIPs are that RJIs are focused on victims, with offenders taking accountability for

their behaviors, and participants in VOM are specifically selected with a predisposition to

success (Androff, 2012; Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015). This study could be added to

the body of literature examining interventions that have been found to be significant in

18

reducing recidivism, thus leading to additional treatment options for offenders of

domestic violence.

Social Change Implications

With statistics showing that domestic violence impacts millions within the United

States and even more internationally, examining ways to reduce recidivism may be

beneficial to victims and other individuals who are affected by this type of crime. In this

study, I sought to add to the current body of literature surrounding domestic violence and

VOM. As previously stated, there was research showing the outcomes of BIPs and their

impact on recidivism rates for domestic violence offenders. There was limited research

examining the use of VOMs in cases of domestic violence. The findings of this study

could be beneficial in the implementation of interventions in cases of domestic violence.

Summary

Recidivism among domestic violence offenders remained an issue impacting the

lives of victims. In addition, offenders are not receiving effective interventions for their

behaviors. BIP continues to be the intervention most commonly used in cases of domestic

violence, despite evidence showing that RJIs are effective in the reduction of recidivism.

The purpose of this quasi-experimental study was to examine any differences in

recidivism between first-time offenders enrolled in a BIP and first-time offenders enrolled

in a VOM program to support the use of additional interventions were determined to be

appropriate in cases of domestic violence.

In Chapter 2, I presented a discussion of literature within the field addressing RJ

and domestic violence, in addition to the theoretical framework of the study. In Chapter

19

3, I addressed the methodology used for this study. Lastly, I reported results in Chapter 4,

followed by a conclusion and summary in Chapter 5.

20

Chapter 2: Literature Review

The purpose of this study was to determine whether there is a difference in the

rate of recidivism between two interventions to domestic violence. Previous researchers

have addressed the prevalence of domestic violence, types of offenders, and effectiveness

of interventions (Apel, 2013; Dutton, 2012; Mills et al., 2013). Mills et al. (2013)

suggested that additional research needs to be conducted to determine whether RJI

programs can be as effective in reducing recidivism in domestic violence offenders as

BIPs have been shown to in previous research.

This chapter contains a literature review focused on domestic violence, BIPs, and

RJI programs. The first section includes background information about domestic

violence, including statistics on prevalence and definitions. In the second section, I

reviewed international, United States, and Ohio laws associated with domestic violence.

The third section includes the interventions explored in this study: VOM (Daly, 2012;

Dhami, 2012; Gromet, 2012; Mills et al., 2013; Weeber, 2012) and BIPs (Herman et al.,

2014; Mills et al., 2013; Pender, 2012). The fourth and final section contains the

theoretical framework for the study, which involves restorative justice and reintegrative

shaming.

Research Strategy

I conducted research for this literature review through an extensive search of

scholarly research and databases. Using the Walden University Library, I searched for

peer-reviewed articles through the following databases: SocINDEX, PsycINFO,

PsycARTICLES, ProQuest Criminal Justice, EBSCO, and Sage Premier.

21

In a comprehensive search, I used the following terms to identify studies

addressing the research problem: recidivism, domestic violence, retribution, intimate

partner violence, victim-offender mediation, batterer intervention program, the first-time

offender, crime, shame, reintegrative shaming, deterrence, and rearrest. The following

sections contain discussions explaining domestic violence, recidivism, and the theoretical

framework of the study.

Domestic Violence

The definition of domestic violence has changed over time in response to changes

in cultural norms and values. Information published by the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC) define the term domestic violence as any harm caused through

physical, sexual, or psychological abuse brought against a current or former intimate

partner (Breiding et al., 2014). Domestic violence was also classified as intimate partner

violence (IPV). Domestic violence victimization is emotional, psychological, and

physical abuse, which has costs for all stakeholders (Pow et al., 2015). Between the years

1980 and 2008, one out of five homicides was the result of domestic violence (Pow et al.,

2015).

Leaving the relationship is not always a solution. When victims attempt to leave

domestic violence offenders, they may be at greater risk of physical harm, which can

even result in death (Pow et al., 2015). With These findings researchers further supported

the need for programs that seek to reduce recidivism in offenders. Most of the domestic

violence offenders who fatally injured victims have been charged with or convicted of a

prior domestic violence crime (Pow et al., 2015).

22

Domestic violence impacts the lives of millions of individuals, with an estimated

4.8 million women being victimized annually worldwide (Sloan et al., 2013). As a result

of these figures, numerous researchers are addressing the impact of domestic violence

and interventions to reduce violence and recidivism rates. As with any crime, there are

reparations for the crime that may restore safety and security to victims and the

community. Gromet (2012) proposed, in his study that satisfaction, or the victims’

feelings toward the interventions (including crimes of domestic violence), may restore

security to the victim and assist in the reduction of recidivism. In addition to these

outcomes, there was an implication for the need of additional research examining

effective interventions for offenders in crimes such as domestic violence (Gromet, 2012).

Prevalence of Domestic Violence Incidents in the United States

Domestic violence is prevalent in the United States, with one estimate indicating

that almost 60% of married women have been abused (Price, 2013). However, domestic

violence expands beyond the victimization of married individuals. There are an estimated

1.3 million women in the United States annually who report a history of victimization,

according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence in 2009 (Herman et al.,

2014). Because many crimes of domestic violence go unreported, these numbers have

been assumed to underrepresent the scope of the problem. These statistics showed that

there is a need to address the domestic violence endemic within the United States, as well

as internationally.

Domestic violence encompasses many acts of violence and intimidation,

including stalking, rape, and assault, as well as psychological abuse and intimidation

23

(Breiding et al., 2014). Breiding et al. (2014), found an estimated 18.3 million women

and 6.5 million men reported stalking in the year 2011. Almost 61% of female victims of

stalking estimated that the offenders were previous intimate partners, and 41% of men

reported that the offenders were intimate partners.

Rape is also considered a crime of domestic violence when it is committed by an

intimate partner. Through a national survey, 8.85% of women and .05% of men reported

being raped by an intimate partner over their lifetimes (Breiding et al., 2014). Statistics

from the same study also indicated that 31.5% of women and 27.5% of men reported

experiencing physical violence over their lifetime (Breiding et al., 2014). While the

number of incidents of reported physical abuse between men and women in the United

States is believed to be close in percentage to each other, there are disparities in reporting

between men and women. Statistics show that women report more abuse and that men are

charged with crimes of domestic violence significantly more often than women (Breiding

et al., 2014).

Victims

Domestic violence is classified as a gender-based crime due to the number of

incidences of violence reported by women (Richards et al., 2014). Its classification as a

gender-based crime does not rule out men experiencing violence, but because women

report abuse more often, there are more reports examining the impact of abuse against

women. Domestic violence can occur regardless of gender, race, and age. In some cases,

these characteristics may play a role in victimization, whereas some characteristics have

24

been found to have a statistically insignificant relationship to the occurrence of domestic

violence (Breiding et al., 2014; Price, 2013; Richards et al., 2014).

Gender. With one in four women being abused yearly, many of the resources for

victims of domestic violence are aimed at providing support and services for women

(Herman et al., 2014). The support for women in regards to domestic violence is

documented by research and gender-based laws that provide protection that meets the

specific needs of women. As a response to the overwhelming number of women reporting

abuse relative to the number of men reporting abuse, there are shelters and other

resources that target women. Though men are victimized, women are more likely to be

physically and psychologically injured by domestic violence than men (Straus &

Gozjolko, 2014).

Although most domestic violence services are geared toward women, it is

estimated that one in seven men are victimized yearly (Herman et al., 2014). This

statistic, though it indicates that domestic violence victimization is not as prevalent

among men as among women, is still significant in validating the need for services for

men. Disparities have been found in the reporting of domestic violence by men

(McKeown, 2014). McKeown (2014) who examined information gathered for use in

studies, as well as the data collected for statistical purposes from arrest records and

intervention programs indicated that there are more men than women among domestic

violence offenders.

Race. Domestic violence can impact men and women of various races. According

to a national study conducted by Breiding et al. (2014), women of multiracial ethnicity

25

were more likely than White and Black women to be victims of domestic violence crimes

of rape and violence. Regarding stalking, American Indian/Alaskan Native women were

more likely to be stalked than women of any other race (Breiding et al., 2014). In a

national study examining domestic violence demographics in youth ages 18-27, 19.15%

of the participants reported domestic violence by an intimate partner (Renner, Whitney, &

Vasquez, 2015). In the findings of the study researchers suggested that White women and

Black men between the ages of 18 and 27 reported higher instances of domestic violence

perpetration than other demographic groups (Renner et al., 2015). Renner et al. (2015)

stated that Black men and White women who reported perpetration of domestic violence

also reported a history of child abuse. Black women and White men reported lower

percentages of perpetration, as well as lower percentages of victimization (Breeding et

al., 2014; Renner et al., 2015). Despite lower percentages for domestic violence

perpetration and victimization, Black women and White men reported higher percentages

of alcoholism, which has been linked to domestic violence perpetration (Lipsky et al.,

2014; Renner et al., 2015).

Age. In a national study by Breiding et al. (2014), victims of domestic violence

were more prevalent in the 18-24 age group. The decrease in victimization directly

correlated with an increase in age. Researchers found that only 4.7% of victims reported

violence over the age of 45 (Breiding et al., 2014). Researchers illustrated that the

findings from this study that victimization decreases as age increases, which correlates

with patterns exhibited by offenders in crimes. Researchers found that as individual’s age,

they are less likely to commit crimes (Breiding et al., 2014).

26

Offenders

The characteristics of individuals can place them at higher risk of becoming an

offender or an abuser. Juodis, Starzomski, Porter, and Woodworth (2014) found that the

characteristics of offenders show trends related to age, race, and psychological and social

factors. When combined, these factors can impact the likelihood of recidivism and the

most appropriate type of intervention. These factors may also have an impact on

intervention programs that are designated for perpetrators of domestic violence.

Age. As with victims, the prevalence of offending decreases as age increases

(Nelson, 2013). There are differences found between women and men offenders that have

an impact on recidivism rates. For women who commit crimes of domestic violence,

evaluation of arrest records has shown that recidivism for crimes of domestic violence

decreases between the ages of 18 and 24 and further decreases in the late 40s (Nelson,

2013). Findings show that as women age, they are less likely to commit crimes of

domestic violence in addition to other violent crimes.

The statistics for men differ regarding the relationship between age and offending.

Between the ages of 18 and 28, there seems to be a slight decrease in recidivism for

women, but it is not significant enough to indicate a correlation between age and reduced

recidivism (Nelson, 2013). The researcher found in contrast to women, the rate of

recidivism in cases of domestic violence has been found to decrease for men over the age

of 28 (Nelson, 2013). Nelson (2013) reported that recidivism regarding domestic violence

for men decreases, in spite of recidivism for other violent crimes increasing for the male

27

population. Based on the findings from previous research, domestic violence offending is

highly correlated with age.

Race. There have been varied results in research concerning the race of domestic

violence offenders. Many researchers have determined that race is not a significant factor

in regard to domestic violence offending (Juodis et al., 2014; Straus & Gozjolko, 2014).

There are disparities found for race, when there is an addition of other factors such as

substance abuse and mental health issues, researchers found to have linkage to violence.

Gender. Though women are more likely to report abuse, in studies researchers

have found that men and women offend in equal amounts (Straus & Gozjolko, 2014).

Straus and Gozjolko (2014) indicated that while men and women offend at similar rates,

men are more likely to cause more physical harm than women. When there is physical

harm resulting in medical or legal intervention, there is more likely to be an arrest

(Bradley, 2015). When individuals are arrested, the statistics are gathered that show that

men are offending more than women. According to Straus and Gozjolko, however, men

who are convicted of crimes of domestic violence are not the only population that is in

need of interventions. There are disparities in what individuals consider to be domestic

violence. In regard to domestic violence, it is more acceptable for women to smack or hit

men than it is for men to strike women (Bradley, 2015). Bradley (2015) found that

despite the acceptance of this type of behavior, these actions are still considered domestic

violence.

28

Mental Health and Substance Abuse

Researchers have shown that there is a significant correlation between a history of

mental illness and substance abuse and perpetration of domestic violence (e.g., Juodis et

al., 2014; Lipsky et al., 2014; McKeown, 2014). Individuals who display symptoms of

psychopathy such as lack of remorse, guilt, and manipulative behaviors have been found

to be more physically aggressive and to have higher recidivism rates in cases of domestic

violence (Juodis et al., 2014). Women who had a history of mental illness or

posttraumatic stress as a result of the previous victimization were more likely to be

domestic violence offenders than women who did not have the same history (McKeown,

2014).

Substance abuse is also a contributing factor in domestic violence (Lipsky et al.,

2014). The researchers reported that binge drinking in Black and White women has a

direct correlation with domestic violence toward an intimate partner (Lipsky et al., 2014).

Furthermore, for Black men and women who have a history of familial violence in

childhood in combination with alcohol abuse, there is an increased likelihood of

victimizing an intimate partner (Lipsky et al., 2014).

Lipsky et al., (2014) found correlation between alcohol use and domestic violence

increased as the number of drinks a person consumes increases (Lipsky et al., 2014). The

use of other substances including cocaine and opiates have also been linked to domestic

violence (Lipsky et al., 2014). In populations of offenders, the researchers found that a

total of 64.9% of domestic violence offenders report drug use, and 75.7% specifically

report alcohol use (Juodis et al., 2014).

29

Domestic Violence Laws

International

Violence against women is a global issue that has been determined to be a human

rights violation by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the European Court of

Human Rights (Ramji- Nogales, 2014). In 1999, the United Nations declared that

domestic violence is an act of violence, and this declaration posed many changes for

various nations (Ramji- Nogales, 2014). One of the main challenges has been that

regarding domestic violence as a gender-based crime violates the norms of some cultures

(Qureshi, 2013). In some European cultures, for instance, submissiveness of women to

men is a norm, and recognition of domestic violence as a human rights issue threatens

cultural practices (Ramji- Nogales, 2014). These cultural issues notwithstanding,

domestic violence according to human rights advocates are considered a violation of

rights and many nations have made great strides since the initial recommendation for

classification of domestic violence as a human rights violation as presented by the United

Nations in 1999 (Qureshi, 2013).

Despite the classification of domestic violence as a human rights violation, some

countries have reported difficulties in the enforcement of anti-domestic-violence laws

(Qureshi, 2013). Difficulties have been presented since the initial recommendation in

1975, before becoming an official declaration by the United Nations (Qureshi, 2013).

Because of the challenges in defining domestic violence and agreement among nations as

a human rights violation, domestic violence was not recognized as a human rights

violation internationally until almost 21st century (Qureshi, 2013). Some of the concerns

30

presented at the United Nations Conferences were the language used in the definition of

domestic violence in the Human Rights Law, which has provided loopholes for countries

in developing laws that impact enforcement (Chaban, 2014).

The U.S. Federal Government. In 1994, The Violence Against Women Act

(VAWA) was passed, providing protection under the law for women impacted by

domestic violence (Weissmann, 2013). The VAWA creators recognized and provided

gender-based support for female victims of abuse at the hands of significant others (U.S.

Department of Justice [USDOJ], 2015). VAWA was reauthorized in 2013, signifying that

domestic violence was still a widespread issue within the United States (Weissmann,

2013). A component of the VAWA Lautenberg Amendment 18 (U.S. Cons. Art. CMXXII)

also impacts gun control for individuals convicted of domestic violence crimes (Price,

2014). According to the USDOJ (2015), domestic violence offenders cannot be in

possession of or obtain weapons in some cases. The possession of weapons includes the

shipping and handling of weapons and ammunition (USDOJ, 2015).

There are concerns with the federal laws regarding victims and offenders. For

instance, there is concern that limitations on gun possession for offenders will impact

judges’ decisions regarding whether to convict individuals of domestic violence crimes

(Price, 2014). The concerns surround judges handling of domestic violence cases, who

may view the loss of gun rights as not appropriate for the crime. These concerns arose

despite statistics showing that a victim of domestic violence is at greater risk of physical

harm, including harm inflicted through the use of a weapon, after the offender is

convicted of a crime (Sherman & Harris, 2013). Another concern relates to the possibility

31

of violating the rights of the victim if the victim does not want the offender to be

convicted or depends on the offender as a primary provider (Sherman & Harris, 2013).

With these concerns, judges and police officers continue to have discretion in the arrest

and conviction (Price, 2014).

The State of Ohio. According to Ohio law, domestic violence is defined as an act

of violence committed or threats to commit violence against a family or household

member (Ohio Government, 2010). Acts of violence in this context included sexual

assault, coercion, forceful detention, or any criminal activity with the intent to cause

bodily harm to a family or household member (Ohio Government, 2010). In the State of

Ohio, there are laws in place to provide protection specifically for victims of domestic

violence. Protection provided under Ohio law (Ohio Revised Codes §2919.25, §2919.26)

includes emergency protection orders which can be tracked nationwide (Ohio

Government, 2010).

Federal law is enforceable by individual states, which means that federal

mandates are applied in addition to a state's domestic violence laws (USDOJ, 2015). As a

result of federal laws being applicable throughout the United States, offenders are held to

the same sanctions throughout the country that were imposed in the original state of the

offense (USDOJ, 2015). As a result of such charges, many offenders are unable to obtain

employment in certain career fields.

Mandatory arrest laws are also applicable within the State of Ohio. Mandatory

arrest laws require that police officers arrest the violators of restraining orders in crimes

of domestic violence (Ohio Government, 2010). In the State of Ohio, offenders can be

32

arrested if they violate protection order as long as the officer believes that they have been

the primary aggressor (Ohio Government, 2010). Mandatory arrest laws in Ohio are

similar to policing agencies in the 21 other States with Mandatory arrest laws as officers

may exercise their discretion, after hearing about the incident from both parties, to

determine who should be arrested even if a protective order has not been granted to the

victim (Ohio Government, 2010). In some cases, if the officer cannot make a decision on

who was the primary aggressor, other parties can be arrested (domestic violence, 2016).

Mandatory arrest has posed some issues regarding advocacy for victims of domestic

violence. One of the concerns is the removal of victims’ rights (Sherman & Harris, 2013).

Mandatory arrest laws may impact the willingness of victims to call emergency

responders for assistance and create increased violence for victims (Price, 2014).

Recidivism

One of the problems in cases of domestic violence, as identified through previous

research, is recidivism (Gavrielides, 2015; Laxminarayan & Woldhuis, 2015; Mills et al.,

2013). In a quantitative study by Sloan et al. (2013) the researchers indicated that current

penalties are not effective in the reduction of recidivism. Through the use of arrest data

collected in North Carolina from 2007, the authors were able to ascertain whether

criminal sanctions were effective in reducing recidivism in domestic violence offenders

(Sloan et al., 2013). Sloan et al. suggested that current sanctions were not effective and

supported the need for further research on interventions for first-time domestic violence

offenders. The research by Nelson (2013) further supported the need for additional

research on domestic violence, in concluding that age is highly correlated with domestic

33

violence, and should be controlled when examining the impact of interventions on

recidivism. In addition, the researchers indicated the need for additional interventions

for offenders because current penalties for crimes of domestic violence have not had a

statistically significant impact in reducing recidivism.

In a quantitative study by Mills et al. (2013), they suggested that restorative

justice interventions are effective in the reduction of recidivism in offenders. The

participants in the study were offenders in Arizona who had been ordered to a RJI, or a

batter’s intervention program. Evidence from follow-up research at 6, 12, 18, and 24

months which showed that offenders had reduced recidivism rates as much, and at the 6-

month period more than offenders in BIPs (Mills et al., 2013). These findings by Mills et

al., (2013) (the limitations include small sample size, locale, and demographics of

offenders) supported claims that despite such programs’ impact on recidivism, there is a

need for research on RJI use in cases of domestic violence when examining recidivism

(Mills et al., 2013).

Researchers examined recidivism in cases of domestic violence offenders and

supported claim that there is a need for additional interventions to support reductions in

recidivism in domestic violence offenders (e.g., Frantzen et al., 2011; Mills et al., 2013;

Sloan et al., 2013). Frantzen et al. (2011) investigated offenders whose cases of domestic

violence were dismissed over a 2-year-period and found that prosecution impacts

recidivism. The handling of domestic violence cases through the criminal justice system,

and stigmatization offenders may receive by society was correlated with offender

recidivism (Frantzen et al., 2011). In order to reduce recidivism in domestic violence

34

offenders, there needs to be additional support from judges and prosecutors in mandating

participation in intervention programs (Frantzen et al., 2011).

RJI and Recidivism Demographics

Demographic characteristics play a role in recidivism. Younger, White men are

more likely to recidivate than men of other races in the same age group (Richards et al.,

2014). The likelihood of recidivism increases if an individual has a history of violent

crime offenses. Offenders who have already been convicted of a crime of domestic

violence according to Richards et al., were more likely to recidivate than individuals who

are first-time offenders (Richards et al., 2014).

Substance abuse is another factor in recidivism; individuals with a history of

substance abuse in combination with a history of violence, according to research have

been found more likely to recidivate than other offenders (Lipsky et al., 2014). The

relationship between the victim and offender also played a role in recidivism. In a

previous study, researchers found that offenders who are married to victims are less likely

to recidivate than nonmarried individuals (Richards et al., 2014). Subsequently, an

offender who shared a child with the victim but does not reside in the same home is at

higher risk of recidivism , as is an offender who was separated from the victim , than an

offender who cohabitates with,is married to,or is divorced from,the victim (Richards et

al., 2014).

Interventions

Domestic violence recidivism rates rank amongst the highest in violent crimes

(Herman et al., 2014). Historically interventions in case of domestic violence according

35

to study findings focused on punitive sanctions to include incarceration (Herman et al.,

2014). Based on the previous studies where researchers focused on recidivism, additional

research needs to be conducted on interventions to determine the effectiveness of

reducing recidivism in a case of domestic violence (Mills et al., 2013). Policing agencies

also need to be included in research as one of the reasons for the lack of use of RJI being

the perceived lack of support by prosecutors and judges, which impact perceived

legitimacy of intervention (Lee, Zhang, & Hoover, 2012).

Interventions are used in the United States, and internationally in cases of

domestic violence. A qualitative study by Boonsit, Piemyat, and Claassen (2012)

examined how cultural and international laws impact the implementation of interventions

in cases of domestic violence in Thailand. In the implications of the study, the

researchers suggested that there needs to be an additional evaluation of interventions to

determine the most efficient in the reduction of recidivism (Boonsit et al., 2012).

In a quantitative study by Gromet et al., (2012) the authors examined victim

satisfaction with RJI programs. The studies researchers examined victim’s satisfaction

with a level of RJI programs, with findings leading one to sugges that victims input in

cases where RJI programs are used, can be impactful on judges sentencing decisions and

address other areas of concern within the criminal justice system to include overcrowded

prisons in the United States (Gromet et al., 2012). Victim participation and previous

interventions research provided support for the use of RJI programs in cases of domestic

violence.

36

Schools of thought

In addition to the programs mentioned above, there are other schools of thought

to the perpetration of domestic violence. Abuse during childhood and adolescences have

been linked to domestic violence perpetration (Lohman, Neppl, Senia, & Schofield, 2013;

O’Leary, Tintle, & Bromet, 2014). It is believed that individuals can socially learn

behaviors, which can be predictive of their future behaviors, as theorized through the

social learning theory (Williams & McShane, 2004). In cases of domestic violence, in

previous studies researchers have found high correlations between domestic violence

perpetration and experience of childhood victimization (Lohman et al., 2013; O’Leary et

al., 2014).

Social Learning theorist proposed that domestic abuse is cyclical and

intergenerational (Lohman et al., 2013). Researchers have also found that abuse in

childhood has been linked to dating violence within traditional college age students 18-

24, which is the age bracket of a high incidence of domestic violence (Sutton et al.,

2014). In order to break the intergenerational cycle of abuse, there would need to be an

identification of children who are being abused physically or psychologically (O’Leary et

al., 2014). Many of these children are diagnosed in adolescence with substance abuse

disorders, and antisocial personality disorders, which has been linked to interpersonal

problems associated with domestic violence (Lawson & Brossart, 2013; Lohman et al.,

2013). According to O’Leary et al. (2014), abused children cases go unreported, making

early interventions more difficult. When problems are identified, approaches such as

individual therapy, and family therapy are intervention methods that could be used to

37

reduce future risk of domestic violence perpetration (Connors, Mills, & Gray, 2013).

Another approach was identifying offenders through assessments such as the Risk Need

Responsivity, which could provide evaluation and suggestions for interventions for

aggressive behaviors (Connors et al., 2013).

Though there is evidence to the social influence of domestic violence, there are

also schools of thought that suggest that propensity to violence may be a result of

development factors (O’Leary et al., 2014). The antisocial behaviors and substance abuse

diagnosis are identified as ill coping factors by theorist developed by children who

experience family violence (O’Leary et al., 2014). Substance abuse has been linked to

domestic violence and the earlier the onset the higher the risk for aggressive behaviors

(Juodis et al., 2014; Lipsky et al., 2014; O’Leary et al., 2014). Researchers found that a

history of mental health diagnosis such as antisocial personality disorder according to

findings from previous studies to be a contributing factor to violence in some offenders as

individuals with this diagnosis lack connection to others and remorse (Juodis et al.,2014;

Lipsky et al., 2014; O’Leary et al., 2014). Researchers have found that characteristics

such as lack of remorse and lack of social connectedness can impact treatment of